In a bold move which challenged the mainstream medical though, three cardiologists have recently asserted that saturated fat does not actually enlarge the risk of a heart attack by clogging up arteries. This declaration has, unsurprisingly, received a great amount of criticism.

In an editorial published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, these cardiologists also argue that the utilization of foodstuffs marketed as “low fat” or “proved to lower cholesterol” in an effort to avoid heart disease is “misguided.”

A crucial previous research study, these scientists believe, “showed no association between saturated fat consumption and all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease, CHD mortality, ischemic stroke or type-2 diabetes in healthy adults.” They, on the other hand, support the notion that a Mediterranean-style diet, coupled with a consistent 22 minutes of walking each day, are the most effective methods to prevent the development of heart problems.

The paper is co-authored by Pascal Meier, a cardiologist at University College London and editor of the journal BMJ Open Heart, Rita Redberg, the editor of the American journal JAMA Internal Medicine, and Aseem Malhotra, a cardiologist at the NHS’s Lister hospital in Stevenage.

Their paper has elicited uncompromising reproach from multiple experts in the field of cardiology and evidence-based medicine. Some argue that the views were not developed using a basis of trustworthy evidence and, thus, would deceive consumers and aggravate the confusion of the general population regarding which foods they should eat and which they should evade.

These three cardiologists further reject the possibility of a diminished consumption of saturated fats as a method to aid in the prevention of heart disease. “There is no benefit from reduced fat, including saturated fat, on myocardial infarction [heart attacks], cardiovascular or all-cause mortality,” declare the authors of the study.

Rather than adopting a low-fat diet, the researchers argue that people intending to slash their risk of heart problems should adhere to “an energy-unrestricted Mediterranean diet (41%) fat supplemented with at least four tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil or a handful of nuts.”

Unfortunately, critics have reacted to this statement by accusing the co-authors of naiveté in overlooking evidence which clearly contradicts their theories. Another major accusation against the authors is that they are attempting to use their study to simplify a vastly complex issue.

Dr. Amitava Banrejee, who is a senior clinical lecturer in clinical data science and honorary consultant cardiologist at UCL, declared: “Unfortunately the authors have reported evidence simplistically and selectively. They failed to cite a rigorous Cochrane systematic review which concluded that cutting down dietary saturated fat was associated with a 17% reduction in cardiovascular events, including CHD, on the basis of 15 randomized trials.”

Dr. Gavin Sandercock, who is the director of research at Essex University, negated the trio’s allegations regarding the benefit of “replacing refined carbohydrates with healthy high-fat foods” because he affirms that this claim is not true, nor is it not based on any standing evidence. “We must continue to research the complex links between fat, cholesterol and heart disease but we must not replace one myth with another,” Sandercock stated.

Christine Williams, a professor of human nutrition at Reading University, described the cardiologists’ dietary advice as being impractical, particularly for less affluent people. “The nature of their public health advice appears to be one of ‘let them eat nuts and olive oil’ with no consideration of how this might be successfully achieved in the UK general population and in people of different ages, socioeconomic backgrounds or dietary preferences,” she explained.

On the other hand, some experts did support the claims of the authors in the controversial study. For example, Dr. Mary Hannon-Fletcher, head of the school of health sciences at Ulster University, acclaimed the conclusions of the study as “the best dietary and exercise advice I have read in recent years. Walking 22 minutes a day and eating real food. This is an excellent public health message.”

“The modern idea of a healthy diet where we eat low-fat and low-calorie foods is simply not a healthy option. All of these foods have been so altered they are anything but healthy. So eating real foods in moderation and exercising daily is the answer to keeping fit and healthy; it’s just too simple a message for the public to take on board,” Fletcher continued on.

Gaynor Bussell, a dietician, and member of the British Dietetic Association, similarly provided the cardiologist trio with certified backing. “Many of us now feel that a predominantly Med-style diet can be healthy with slightly more fats and fewer carbs, provided the fats are ‘good’ – such as in olive oil, nuts or avocados,” she said.

Despite her overall praise, Bussell argues that saturated fats should comprise no more than 11% of anyone’s food intake; this is considerably less than the 41% fat level advocated for by the co-authors of the study.

Although carbohydrates should concretely be a portion of every meal, people should regularly ingest high fiber or whole grain versions of such, according to Bussell.

Williams additionally critiqued the BJSM under the allegation that it was publishing opinions with the intent of depicting saturated fats as “innocent” in the causation of heart disease in an effort to produce headlines—and thus attract a larger audience. “Some would argue the journals have a very credible business model based on attracting controversy in an area of great importance to public health where clarity, not confusion, is required,” she said.

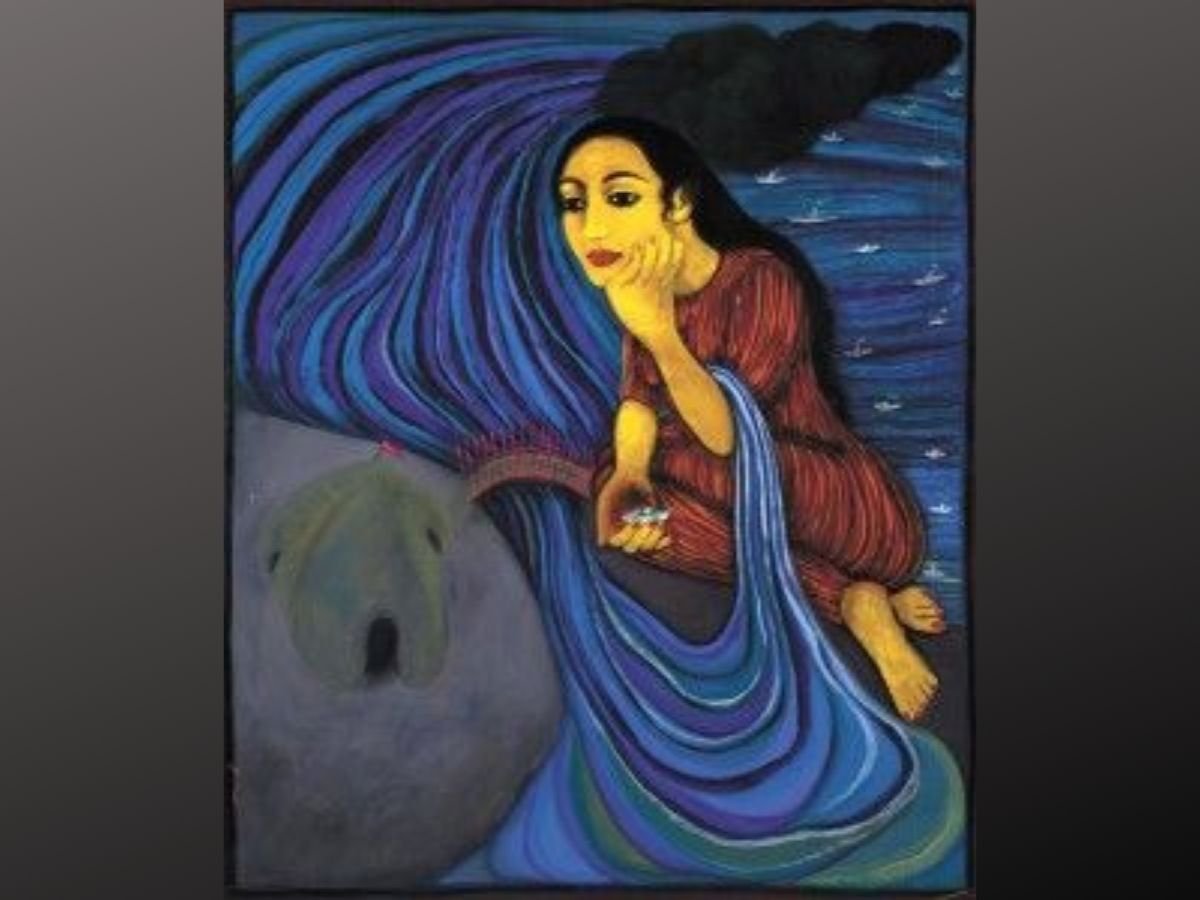

Featured Image via Wikimedia.